|

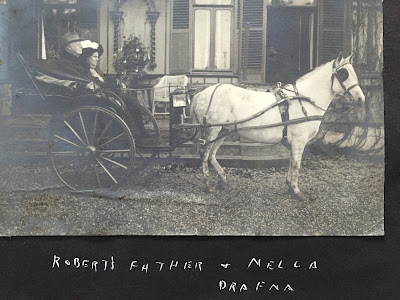

| Charles Boissevain with his daughter Nella Hissink in front of Drafna. Notation by Anne Boissevain, Robert's second wife, in the album she kept. |

Suburban Boissevain homes in the 1920s and 1930s were clustered in the Amsterdam area – especially in Naarden and Haarlem.

In the summer many of them went to their beach houses in Zandvoort (recently renamed "Amsterdam Beach") on the North Sea – at the same longitude as Amsterdam.

The extended Boissevain and van Hall families would gather as a single family at celebrations such as a wedding (bruiloft), or a wedding anniversary (huwelijksverjaardag) of the family patriarch and matriarch.

|

| Map 1. The Boissevain houses went from Zandvoort on the coast to Haarlem and Amsterdam, then east to Naarden. |

The most famous homes were Drafna in Naarden, home of Charles and Emily Boissevain; or Astra and the Kolkhuis (which I visited several times) in Hattem, homes of Jan and Hester van Hall.

Families related closely to the Boissevains, all of them I think with more than one intermarriage among cousins, include the den Texes, van Halls, van Lenneps and van Tienhovens.

With Charles Boissevain in February 2015, I visited many places where members of the family lived or worshipped in the 20th Century, and even some homes where relatives still lived and welcomed us.

Homes are concentrated in a line from Zandvoort on the west coast to Haarlem, Amsterdam and Naarden (see Map 1).

The line continued east from Amersfoort, where Teau Boissevain de Beaufort, lived, to Hattem and Zwolle. The van Halls moved to Zwolle for health reasons, because the higher ground to the east makes it drier than areas closer to Amsterdam. The van Halls lived first in Zwolle and then at the Kolkhuis in Hattem (see Map 2).

Relatives who lived off the Zandvoort-to-Zwolle band include Nella Boissevain Hissink, who lived in the capital of Friesland, Leeuwarden.

Amsterdam

The house at Corellistraat 6 was the home of Jan "Canada" Boissevain and Mies van Lennep Boissevain. Their two eldest children were Gijs ("Gi") and Jan Karel ("Janka") Boissevain.

|

| My mother's Aunt Hester Boissevain van Hall ("Tante Hessie") lived in "Het Kolkhuis" in Hattem. |

Homes are concentrated in a line from Zandvoort on the west coast to Haarlem, Amsterdam and Naarden (see Map 1).

The line continued east from Amersfoort, where Teau Boissevain de Beaufort, lived, to Hattem and Zwolle. The van Halls moved to Zwolle for health reasons, because the higher ground to the east makes it drier than areas closer to Amsterdam. The van Halls lived first in Zwolle and then at the Kolkhuis in Hattem (see Map 2).

Relatives who lived off the Zandvoort-to-Zwolle band include Nella Boissevain Hissink, who lived in the capital of Friesland, Leeuwarden.

Amsterdam

The house at Corellistraat 6 was the home of Jan "Canada" Boissevain and Mies van Lennep Boissevain. Their two eldest children were Gijs ("Gi") and Jan Karel ("Janka") Boissevain.

(Postscript, June 6, 2021: Many Boissevains had homes and offices along the canals in central Amsterdam. Some of these areas are suffering from the deterioration of the pilings that support the canal-side buildings. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/06/05/world/europe/amsterdam-crumbling-infrastructure-canals.html.)

Eindhoven

Engelien de Booy lived here - I visited her at her home before she died.

Haarlem

In the Bentveldsweg, within 100 meters of each other, live or have lived four families with van Hall descendants:

The family then moved to Zandvoort, by the seashore, where the war began.

We went nearby, to Beelslaan 3 in Haarlem, to pay a visit to Mary-Ann van Hall Boon, daughter of Wally van Hall, and her husband.

Hattem

Hattem is near Zwolle, quite a distance from Amsterdam. Hester van Hall's Kolkhuis was here. I attended several celebrations of birthdays during our summer visits to Holland after World War II. The young visitors were roped into participating in skits for the enjoyment of older family members.

Naarden

Drafna was built on an enormous farm that is an hour southeast of Amsterdam, in Naarden, near the Naarden-Bussum train station. It was on the Zuyder Zee, but much of the land there was reclaimed. Naarden is a former coastal fortress town with buildings dating back to the 16th century. Charles and Emily moved there in 1897.

The house is legendary because so many children (eleven) grew up there and so many grandchildren (50), including my mother, went there for many visits.

My mother remembers the Golden Wedding Anniversary of her grandparents Charles and Emily in 1916, when she was 8 years old.

Large tents were set up to accommodate the crowds. She was struck by the importance of her grandparents and the importance of a Golden Wedding. She told me in 1982, the year of her own Golden Wedding:

Hilda was too Dutch-looking and introspective for Emily. Emily preferred the grandchildren who looked the most Irish, like the six children of Robert with his first wife, Irishwoman Rosie Phibbs - or Teautie de Beaufort, who looked (as her mother Teau did) Irish.

But Hilda was a favorite of her grandfather Charles, because she was a writer like him, and was precociously clever at drawing. Hilda's first publisher was in fact her grandfather, in his newspaper, the Algemeen Handelsblad.

Mary ("Polly") Barker, an English nurse, served the family from 1873 until her death in 1929. All of the eleven children and their 50 grandchildren were very fond of Polly, which suggests that Polly looked after all of the children, including those who did not measure up to Emily's expectations. My mother said she preferred Polly to Emily.

The 40-acre property outside was full of wonders One side of the driveway at Drafna was lined with lime trees. Elsewhere were many chestnut trees, which yielded edible chestnuts. Hilda got her taste there for marrons glacées, candied chestnuts, which reminded her of Drafna. The lawn was deep in clover. The property included a tennis court.

The farm included a pond and a stable and an array of animals beloved by the grandchildren - a donkey, a goat, a white horse (which had its own carriage to pull), fish and birds. The gardener was named Hein and Hilda remembers him forever having complaints about the young visitors like her.

As the children of Charles and Emily formed families of their own, they were sold or allowed to use pieces of the farm, so that five of the eleven Boissevain children, and their children, have lived in the area. The six exceptions were:

Eindhoven

Engelien de Booy lived here - I visited her at her home before she died.

Haarlem

|

| Emmaplein 2, where Robert and Sonia lived until 1936. |

In the Bentveldsweg, within 100 meters of each other, live or have lived four families with van Hall descendants:

- Zonnehof was built for Charles's great-uncle Aat van Hall (father of Gijs and Wally van Hall), who raised ten children there between 1897 and about 1915. When I visited in 2015 it was inhabited by their daughter Hester van Hall Dufour and Raimond Dufour.

- De Popelhof was the home of great-aunt Han van Hall Vening Meinesz, youngest sister of Jan and Aat and Suze van Hall van Tienhoven, mother of Corrie.

- Sparrenhof was formerly inhabited by Maurits and Elsa van Hall and after his death by his daughter Ellen van Hall Wurpel, who is secretary of the van Hall Foundation. She invited us in for a visit.

- Biekaer after the war was where Charles's mother, Sonia, went with her six children.

The family then moved to Zandvoort, by the seashore, where the war began.

We went nearby, to Beelslaan 3 in Haarlem, to pay a visit to Mary-Ann van Hall Boon, daughter of Wally van Hall, and her husband.

Hattem

Hattem is near Zwolle, quite a distance from Amsterdam. Hester van Hall's Kolkhuis was here. I attended several celebrations of birthdays during our summer visits to Holland after World War II. The young visitors were roped into participating in skits for the enjoyment of older family members.

Naarden

Drafna was built on an enormous farm that is an hour southeast of Amsterdam, in Naarden, near the Naarden-Bussum train station. It was on the Zuyder Zee, but much of the land there was reclaimed. Naarden is a former coastal fortress town with buildings dating back to the 16th century. Charles and Emily moved there in 1897.

The house is legendary because so many children (eleven) grew up there and so many grandchildren (50), including my mother, went there for many visits.

|

| Drafna, Naarden, in 1933. The 14-room two-story Norwegian chalet was home to Charles and Emily Boissevain and their 11 children. |

Large tents were set up to accommodate the crowds. She was struck by the importance of her grandparents and the importance of a Golden Wedding. She told me in 1982, the year of her own Golden Wedding:

Everyone sat at long tables under the tent awnings. I was given an ice cream cone with a photo of my grandparents stuck in it. I don't know whether all 50 grandchildren got this special treat. During the afternoon events, I remember the smell of hay everywhere. The afternoon ended with skits and performances, but I don't remember them and maybe they were only for grownups.My mother also told me that the grandchildren would often, on arrival at Drafna, make a bee-line to their library where many wonders could be found.

I earned a scolding from my Granny for doing so: "The first thing you do when you visit anywhere, is to present yourself to your hostess and greet her. I didn’t even know you had arrived." So in future I did as she told me. Since the drawing room was next door to the library, not too much time was wasted. But I have to confess I was not the most popular guest. Those who had not learned to read yet fared much better.The late Engelien de Booy told me before she died that there was a dark side to Drafna. It was full of gaiety and fun partly because that is what Emily wanted to see. Emily liked to know that her children were successful. She positively disliked introspective children – like Engelien, who went on to earn her doctorate – or, even worse, children who seemed slow or stupid.

Hilda was too Dutch-looking and introspective for Emily. Emily preferred the grandchildren who looked the most Irish, like the six children of Robert with his first wife, Irishwoman Rosie Phibbs - or Teautie de Beaufort, who looked (as her mother Teau did) Irish.

But Hilda was a favorite of her grandfather Charles, because she was a writer like him, and was precociously clever at drawing. Hilda's first publisher was in fact her grandfather, in his newspaper, the Algemeen Handelsblad.

|

| Polly Barker, Drafna's Resident English Nurse-Governess (Mary Poppins). |

The 40-acre property outside was full of wonders One side of the driveway at Drafna was lined with lime trees. Elsewhere were many chestnut trees, which yielded edible chestnuts. Hilda got her taste there for marrons glacées, candied chestnuts, which reminded her of Drafna. The lawn was deep in clover. The property included a tennis court.

The farm included a pond and a stable and an array of animals beloved by the grandchildren - a donkey, a goat, a white horse (which had its own carriage to pull), fish and birds. The gardener was named Hein and Hilda remembers him forever having complaints about the young visitors like her.

As the children of Charles and Emily formed families of their own, they were sold or allowed to use pieces of the farm, so that five of the eleven Boissevain children, and their children, have lived in the area. The six exceptions were:

- Hester and Jan van Hall, who moved to Zwolle and then Hattem to be on higher ground and therefore in a drier climate. The van Hall homes in Zwolle were called Astra and Little Astra, where my mother's family lived for a few years. Hester van Hall later moved to the Kolkhuis (Lake House) in Hattem, where the family came several times to parties, and I visited her alone in 1959. She would put on her cap and come out to see her guests with tea.

- Nella and Theodor Hissink, moved to Leeuwarden in Friesland. This is the town that is drawn by my mother in A Day on Skates. A Dutch edition of this book is needed! It should have the name A Day on Skates in Friesland.

- Teau and Fik de Beaufort, who moved to Amersfoort. Fik de Beaufort had a ducal title in France but preferred to live in Holland. Teau was the youngest of the 11 children of Charles and Emily and died first, tragically, in 1922.

- The three youngest Boissevain boys - who found Holland constraining and married American women. Robert was the first to leave - he remarried (he left his wife Rosie and their six children in Holland, which was a scandal, but my mother said there were extenuating circumstances) an American woman who was the assistant to philanthropist Alva Vanderbilt Belmont; they lived on a chicken farm in upstate New York. Eugen followed Robert and married two truly great American Bohemian women - Inez Milholland and Edna St. Vincent Millay. Jan went to Java to work for Robert in 1914 and eventually married another Bohemian, an American actress, Charlotte Ives, and they lived in the Cap d'Antibes, where I visited her in July 1962 – she took me on an excursion into Cannes to visit a local car dealer so she could buy a new car.

When Charles Boissevain died in 1927, Emily at first stayed at Drafna with Polly. They lived in different parts of the house and entertained separately. After Polly's death, Emily moved to the home of Charles E. H. Boissevain, her eldest son, until her own death in 1931. Drafna was sold to a Theosophical School, was used as a rugby team center, and was broken down before World War II (some say it burned down) to be replaced by a stone house. In the 1970s it was sold to a Dutch company and as of 1982 was a retreat and training center.

Zandvoort

On the South Boulevard in Zandvoort, Charles showed me the place where his family house De Duinhut formerly was. The houses are not there any more because they were were knocked down to make way for coastal fortifications. According to Joseph Goebbels in his Diaries, Hitler was sure that the invasion of Europe by the Allies would come via the beaches of Holland.

Along a 10-km. route (the shortest way) Bob, Marit and Son Boissevain had to go on their bike every day to their school in Overveen, the Lycée Kemmerer. By the end of the war most of the schools were closed.

Zandvoort

On the South Boulevard in Zandvoort, Charles showed me the place where his family house De Duinhut formerly was. The houses are not there any more because they were were knocked down to make way for coastal fortifications. According to Joseph Goebbels in his Diaries, Hitler was sure that the invasion of Europe by the Allies would come via the beaches of Holland.

Along a 10-km. route (the shortest way) Bob, Marit and Son Boissevain had to go on their bike every day to their school in Overveen, the Lycée Kemmerer. By the end of the war most of the schools were closed.