|

| "No regret for the past. No fear of the future." |

My grandmother Olga Boissevain's family were Huguenots – French Protestants who followed John Calvin's doctrine of predestination, changing the status of business people from one of toleration to one of divine grace.

This was naturally an attractive religion for business people in France, who had been pilloried by the Catholic Church for having become too rich to enter the Kingdom of Heaven.

The Boissevains originally lived in Bergerac in the Dordogne, France but had to leave because the Catholic king Louis XIV became uneasy at the growth of Huguenot power.

The Boissevains Escape and Some Go to Holland

No one, of course, would leave the gorgeous Dordogne area voluntarily. They had to be ejected. The Boissevains were booted out, a minority within France that was no longer welcomed.

The name Boissevain comes from the boxwood tree (Buxus) that is common in the Dordogne. In that part of the world, one tree means in front of the house means "Go Away”. Two trees means “Come and Go as You Please”. Three trees together means “Welcome”.

The first of the Boissevain clan was Lucas Bouyssavy (1660-1705), who made his Roman name into a more French name by changing it to Boissevain. He was a French Calvinist, who were called Huguenots because of an early leader named Hugues.

After the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes by Louis XIV in 1685, Lucas escaped to Holland in 1688, hiding among wine barrels in the hold of a ship from Bordeaux to Amsterdam. He began his life as an immigrant by teaching subjects like bookkeeping, French and architectural drafting. He kept the faith, attending the Walloon (francophone) church in Amsterdam.

Calvin went beyond Martin Luther in objecting to an anti-business bias in Roman Catholic doctrine. He built on preachings of St. Augustine to develop a doctrine of predestination, in which worldly wealth is a sign of divine favor. For from being an obstacle to entering the Kingdom of Heaven, wealth was a sign of the elect.

Calvin went beyond Martin Luther in objecting to an anti-business bias in Roman Catholic doctrine. He built on preachings of St. Augustine to develop a doctrine of predestination, in which worldly wealth is a sign of divine favor. For from being an obstacle to entering the Kingdom of Heaven, wealth was a sign of the elect.With this wind in their sails, the Huguenots were successful in France, and at their height they accounted for half of the nobility and half of the artisans. But the Catholic Church fought back:

- In 1534, the Society of Jesus (Jesuits) was created by Spaniard St. Ignatius of Loyola, as a counter-Reformation group with a military-style organization, reporting directly to the Pope.

- In 1572, to end a French civil war between Catholics and the Protestant Huguenots, Catherine de' Medici, wife of Henry II, called Huguenot leaders to Paris on St. Bartholomew's Day, ostensibly for peace negotiations. She then had all of these leaders massacred in their beds during the night.

- In 1685, Louis XIV became impatient with the Huguenots' mobilizing an "armed political party" (William Langer, Encyclopedia of World History, 1948, p. 386) under the protection of a promise of religious freedom by Henry IV. Louis revoked this promise, the Edict of Nantes.

The results of the Edict's being revoked were disastrous for France.The Boissevain family well remembers its history of religious persecution, not least and the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre. This has meant - as in many other families that have faced persecution - the family retains a core value of fighting for justice, and a consciousness of the cost of this value. The Huguenot religious beliefs have been diluted and modified through shifts to a more secular society as well as conversions and marriages (my mother, for example, converted to Catholicism). The core family value is expressed in the Boissevain motto

Ni regret du passé, Ni peur de l’avenir. No regret for the past, because its costs are the price we must pay. No fear of the future, because we are here to face forward.The Boissevain Family in Holland

After the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes by Louis XIV in 1685, Lucas escaped to Holland in 1688, hiding among wine barrels in the hold of a ship from Bordeaux to Amsterdam. He began his life as an immigrant by teaching subjects like bookkeeping, French and architectural drafting. He kept the faith, attending the Walloon (francophone) church in Amsterdam.

Through the church he met Marthe Roux, who escaped with her mother and sister in a hay wagon in 1686. Marthe Roux's mother kept her daughters quiet even when soldiers at the border stuck their bayonets into the hay. Marthe's mother was stuck in the leg but was soundless, even having the presence of mind to wipe her blood off the bayonet with her skirt. Of such stuff were the Boissevain women made. No wonder they were leaders in the woman suffrage movement in Holland.

She and Lucas married in 1700 and had a son Jeremie Boissevain (1702-1762), who continued his father's business of teaching drafting and English, and worked as a bookkeeper. He had a son Gideon Jeremie Boissevain (1741-1802), who was a merchant and accountant (bookhoeder). He had a son Daniel Boissevain (1772-1834), who became a ship-owner, living in the middle of Amsterdam on the Herengracht. He married a socially prominent woman and they had 14 children, including five males from whom most of the other Boissevains in the world appear to be descended (the others descend from Daniel's brother Henri Jean Boissevain).

The Boissevains in Holland did well with their Huguenot appetite for commerce. They were involved in seagoing activities - Dutch Navy admirals, shipping magnates, sea rescue directors, shipbuilding, and banking. The family was extremely musical and creative, and generated not only Bankers and Boaters, but Bohemians as well. The Boissevains were a major force for the creation of the concert hall (Concertgebouw) in Amsterdam. I heard this from my mother and from a Dutch relative who was close to her, the late Sacha Boissevain (see February 2010 post).

|

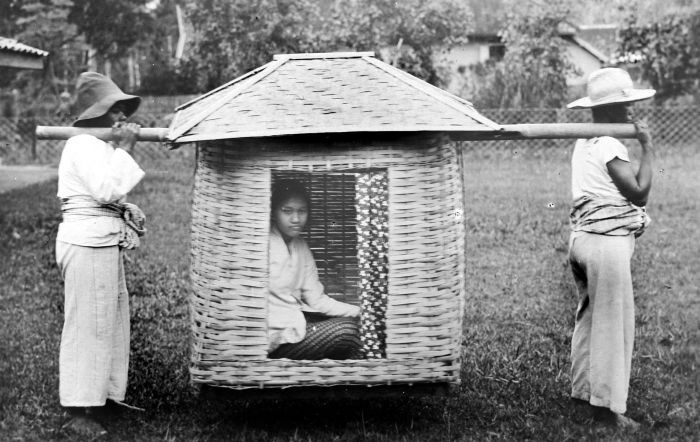

| Emily Heloise MacDonnell Boissevain and her five sons, c 1910. L to R, seated, front row: Charles E. H., Emily, and Alfred. Standing: Jan Maurits, Eugen and Robert (all three went to USA). |

The Jantjes - Boaters and Bankers

Jan Boissevain (1836-1904, NP p. 52) was the fifth child of Gedeon and was a Boater and Banker. My mother used to call his nine children and their descendants the Jantjes (little Jans). The term is formally identified in the Dutch Boissevain Foundation Bulletin. The Jantjes were very important in the Dutch Resistance in World War II.

- His third child Charles Daniel Walrave Boissevain was a Boater, going from the Dutch Navy to serve as Consul-General to Canada (1866-1944, NP p. 55); his son Jan "Canada" Boissevain was born in Montreal, hence the nickname; Jan Canada's sons Gi and Janka were leaders of the armed resistance.

- His seventh child, Petronella Johanna Boissevain, married Adriaan Floris ("Aat") van Hall (1870-1959, NP p. 54), and their children included the Dutch Resistance leader Walraven van Hall. Aat van Hall's twin brother Floris Adriaan ("Floor") van Hall died during the early part of World War II, and Aat was named as his executor.

http://nyctimetraveler.blogspot.com/2015/02/who-were-emily-helose-macdonnell-and.html

Charles Boissevain (1842-1927, NP p. 67), sixth child of Gedeon, was a Bohemian, publisher of the leading Dutch newspaper and, for some years, the most popular journalist in Holland, writing a column called Van Dag Tot Dag ("From Day to Day"). He married an Anglo-Irish woman, Emily Heloise MacDonnell, in 1867. His original first name was Karel, the Dutch version of Charles. But since he married an Irish girl, Emily Heloise MacDonnell (1844-1931), whom he met when covering the International Exhibition of 1865, he anglicized his name to Charles. He got sick while at the Exhibition, and Emily's parents brought him home to recover. Emily looked after him and they fell in love.

The MacDonnells came from Scotland in the 15th century. Colla MacDonnell settled in Tynekill Castle and was provided with gallowglasses (government soldiers) to keep order. They were powerful people in the county. My nephew Christ Oakley has visited what is left of Tynekill. James MacDonnell unfortunately forfeited the property and privileged position that Colla had acquired by rebelling against the British King in 1641. After that the MacDonnells had to have a profession or a government appointment. Richard MacDonnell (1787-1867) was Provost of Trinity College Dublin from 1852 until his death. He married Jane Graves, daughter of the Very Rev. Richard Graves who was descended from Duc Henri de Montmorency, executed in France in 1652. One of Richard MacDonnell's sons, Hercules Henry Graves MacDonnell (1819-1900) married Emily Anne Moylan in 1842, eloping to be wed by the blacksmith of Gretna Green - their second child was Emily MacDonnell. Emily Moylan (1852-1883) was the only child of Denis Creagh Moylan (1794-1849) and Mary Morrison King, who was the out-of-wedlock daughter of George, Third Earl of Kingston, who can be traced back to John of Gaunt and Edward III.

Charles was outspoken and liberal. He took the side of the Boers against British aggression in a book-length "Letter to the Duke of Devonshire" and upset his wife's relatives in Ireland. When Emily tried to defend the British, her daughters called her a Rooinek ("Redneck"), which is what the Boers called the British soldiers. Charles never seemed to have enough money, certainly not enough to match his vanity, but with he help of occasional inheritances they brought up eleven children in style. The Bohemians among the Boissevains never seemed to match the affluence of the Banker-Boaters like Jan, and the women among the Bankers were occasionally scandalized by the behavior of the Bohemians.

Charles and Emily had 11 children and they and their descendants are called the Kareltjes or Charletjes (little Charleses). The Boissevain Foundation Bulletin spells it Charles-tjes, but the English language avoids having three consonants in a row and I am spelling it the way my mother did, without the hyphen:

The MacDonnells came from Scotland in the 15th century. Colla MacDonnell settled in Tynekill Castle and was provided with gallowglasses (government soldiers) to keep order. They were powerful people in the county. My nephew Christ Oakley has visited what is left of Tynekill. James MacDonnell unfortunately forfeited the property and privileged position that Colla had acquired by rebelling against the British King in 1641. After that the MacDonnells had to have a profession or a government appointment. Richard MacDonnell (1787-1867) was Provost of Trinity College Dublin from 1852 until his death. He married Jane Graves, daughter of the Very Rev. Richard Graves who was descended from Duc Henri de Montmorency, executed in France in 1652. One of Richard MacDonnell's sons, Hercules Henry Graves MacDonnell (1819-1900) married Emily Anne Moylan in 1842, eloping to be wed by the blacksmith of Gretna Green - their second child was Emily MacDonnell. Emily Moylan (1852-1883) was the only child of Denis Creagh Moylan (1794-1849) and Mary Morrison King, who was the out-of-wedlock daughter of George, Third Earl of Kingston, who can be traced back to John of Gaunt and Edward III.

Charles was outspoken and liberal. He took the side of the Boers against British aggression in a book-length "Letter to the Duke of Devonshire" and upset his wife's relatives in Ireland. When Emily tried to defend the British, her daughters called her a Rooinek ("Redneck"), which is what the Boers called the British soldiers. Charles never seemed to have enough money, certainly not enough to match his vanity, but with he help of occasional inheritances they brought up eleven children in style. The Bohemians among the Boissevains never seemed to match the affluence of the Banker-Boaters like Jan, and the women among the Bankers were occasionally scandalized by the behavior of the Bohemians.

Charles and Emily had 11 children and they and their descendants are called the Kareltjes or Charletjes (little Charleses). The Boissevain Foundation Bulletin spells it Charles-tjes, but the English language avoids having three consonants in a row and I am spelling it the way my mother did, without the hyphen:

- His eldest son, Charles Ernest Henri Boissevain (1868-1940, NP p. 69) married a famous Dutch suffragist Maria Barbera Pijnappel (one of many suffragists in the family); they had ten children of whom the third was Robert Lucas Boissevain, who was bankrupted by the Nazis and became a Dutch Resistance leader. In a house in Haarlem owned by his wife's recently deceased uncle Aat (Floris Adriaan van Hall), he lodged himself, his wife, six children (including one hiding from the forced-labor razzia), plus four Jewish hideaways.

- The third daughter, Olga Emily Boissevain (my grandmother), married a naval officer, Bram van Stockum. They had a daughter, Hilda van Stockum, and two sons. The middle son, Willem van Stockum, worked with Einstein, volunteered to be a bomber pilot, and was killed in his sixth bombing mission over France during the week of D-Day (a book was written about him in 2014, Time Bomber, by Robert Wack, a U.S. Army major and pediatrician).

- The fourth daughter, Hilda Boissevain was born July 12, 1877. She was the younger of the middle two girls among the Charletjes. The first two of Charles’ daughters, Mary and Hester (Hessie) made conventional marriages, with no interest in higher education. The second two–Hilda and Olga–were interested in higher education but had to fight for it. The third set of two, Nella and Teau, both went on to university without thinking twice about it. Hilda married Hendrik (“Han”) de Booy, from a long line of Dutch naval officers, including some vice-admirals, bonding with the Boaters among the Boissevains. In 1929-31, when Hilda van Stockum was in Amsterdam studying art, she stayed with the de Booy family and painted the portrait of their daughter Engelien. Han became the head of the Dutch Lifeboat Company, a sea-rescue organization. He also worked for the Amsterdam Concertgebouw as an officer, during which time his brother-in-law Charles E. H. Boissevain stepped off the Board to avoid a conflict of interest. The de Booys had four children: (1) Hendrik Thomas (Tom) de Booy, b. December 26, 1898, who married Ottoline Gooszen and followed his father as Secretary, then Director of the Dutch Lifeboat Company. (2) Alfred de Booy, b. May 29, 1901, married Sonja van Benckendorff, from Byelarus, the daughter of a landowner near Bakou. (3) Olga Emily de Booy, b. March 14, 1905, married John Gottlieb van Marle and they had three children (some cousins of the van Marles were active in the Resistance). (4) Engelina ("Engelien") Petronella de Booy, b. June 17, 1917 as mentioned was a friend of my mother Hilda van Stockum; she married Dr. Marcus Frans Polak at the beginning of the war and thereby saved his life because he was Jewish and would have been deported if not married to her. After the war they were divorced because he couldn’t carry the burden of knowing she saved his life. But, Engelien says, they remained very good friends to the end of their lives. [See also https://nyctimetraveler.blogspot.com/2015/02/the-first-year-of-dutch-occupation.html.]

Hester Boissevain den Tex (1842-1914, NP p. 49), twin of Charles, married Nicolaas Jacob den Tex in 1866. They had ten children, one of whom married a Boissevain cousin!

References

Benoit, Histoire de l'Edit de Nantes (5 vols., Delft, 1693);

Browning, History of the Huguenots (London, 1840); PUAUX, Histoire de la Reformation francaise (7 vols., Paris, 1859);

Coignet, L'evolution du protestantisme francais au XIX siecle (Paris, 1908);

Encyclopedie des sciences religieuses, ed.

de Beze, Histoire ecclesiastique des eglises reformees au royaume de France (2 vols., Toulouse, 1882).

de la Tour, Les Origines de la Reforme (2 vols. already issued, Paris, 1905-9).

Dégert, Antoine. (1910). "Huguenots." The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Co. Retrieved Dec. 14, 2015 from New Advent: www.newadvent.org/cathen/07527b.htm

Encyclopedia Bitannica, 11th ed., 1910. "Huguenots. http://www.britannica.com/topic/Huguenot.

Laval, Compendious History of the Reformation in France (7 vols., London, 1737);

Lichtenberger, Paris, 1877-82), s.v.; HAAG, La France protestante (10 vols., Paris, 1846; 2nd ed. begun in 1877); Bulletin de l'histoire du protestantisme francais; Revue chretienne;

Smedley, History of the Reformed Religion in France (3 vols., London, 1832);

Other Chapters

The above post is a draft of Chapter 1 of a book. The other chapters are listed with links in The Boissevain Family in the Dutch Resistance, 1940-45.

Benoit, Histoire de l'Edit de Nantes (5 vols., Delft, 1693);

Browning, History of the Huguenots (London, 1840); PUAUX, Histoire de la Reformation francaise (7 vols., Paris, 1859);

Coignet, L'evolution du protestantisme francais au XIX siecle (Paris, 1908);

Encyclopedie des sciences religieuses, ed.

de Beze, Histoire ecclesiastique des eglises reformees au royaume de France (2 vols., Toulouse, 1882).

de la Tour, Les Origines de la Reforme (2 vols. already issued, Paris, 1905-9).

Dégert, Antoine. (1910). "Huguenots." The Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Co. Retrieved Dec. 14, 2015 from New Advent: www.newadvent.org/cathen/07527b.htm

Encyclopedia Bitannica, 11th ed., 1910. "Huguenots. http://www.britannica.com/topic/Huguenot.

Laval, Compendious History of the Reformation in France (7 vols., London, 1737);

Lichtenberger, Paris, 1877-82), s.v.; HAAG, La France protestante (10 vols., Paris, 1846; 2nd ed. begun in 1877); Bulletin de l'histoire du protestantisme francais; Revue chretienne;

Smedley, History of the Reformed Religion in France (3 vols., London, 1832);

The above post is a draft of Chapter 1 of a book. The other chapters are listed with links in The Boissevain Family in the Dutch Resistance, 1940-45.